Previously on Screenface.net:

I’ve been participating in an online “hack” looking at “Digital is not the future – Hacking the institution from the inside” with a number of other education designers/technologists.

I shared some thoughts and summarised some of the discussions tied to the issues we face in supporting and driving institutional change, working with organisational culture and our role as professional staff experts in education design and technology.

There’s still much to talk about. Technology and what we need it to do, practical solutions both in place and under consideration / on the wishlist, further questions and a few stray ideas that were generated along the way.

Technology:

Unsurprisingly, technology was a significant part of our conversation about what we can do in the education support/design/tech realm to help shape the future of our institutions. The core ideas that came up included what we are using it for and how we sell and instill confidence in it in our clients – teachers, students and the executive.

The ubiquity and variety of educational technologies means that they can be employed in all areas of the teaching and learning experience. It’s not just being able to watch a recording of the lecture you missed or to take a formative online quiz; it’s signing up for a course, finding your way to class, joining a Spanish conversation group, checking for plagiarism, sharing notes, keeping an eye on at-risk students and so much more.

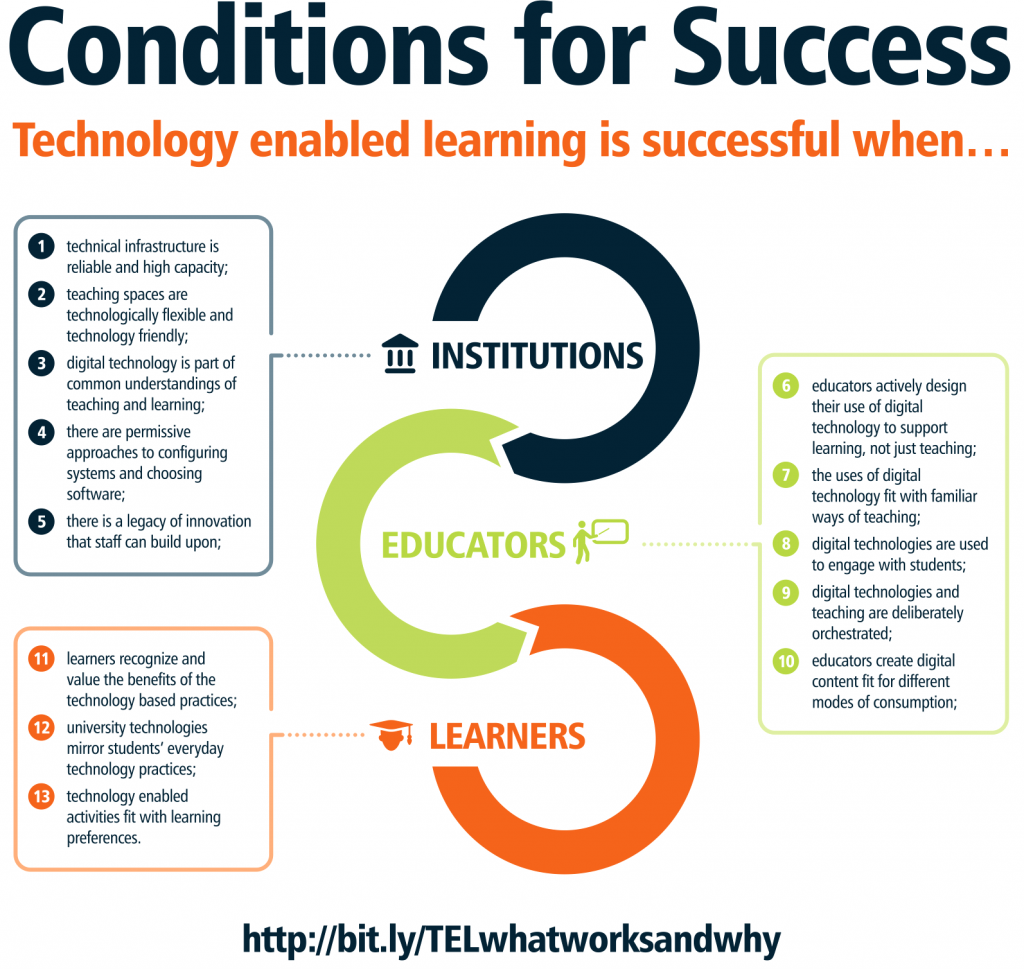

It’s a fine distinction but Ed Tech is bigger than just “teaching and learning” – it’s also about supporting the job of being a teacher or a learner. I pointed out that the recent “What works and why?” report from the OLT here in Australia gives a strong indication that the tools most highly valued by students are the ones that they can use to organise their studies.

Amber Thomas highlighted that “…better pedagogy isn’t the only quality driver. Students expect convenience and flexibility from their courses” and went on to state that “We need to use digital approaches to support extra-curricular opportunities and richer personal tracking. Our “TEL” tools can enable faster feedback loops and personalised notifications”

Even this is just the tip of the iceberg – it’s not just tools for replicating or improving analog practices – the technology that we support and the work we do offers opportunities for new practices. In some ways this links back closely to the other themes that have emerged – how we can shape the culture of the organisation and how we ensure that we are part of the conversation. A shift in pedagogical approaches and philosophies is a much larger thing that determining the best LMS to use. (But at its best, a shift to a new tool can be a great foot in the door to discussing new pedagogical approaches)

“It is reimagining the pedagogy and understanding the ‘new’ possibilities digital technologies offer to the learning experience where the core issue is” (Caroline Kuhn)

Lesley Gourlay made a compelling argument for us to not throw out the baby with the bathwater when it comes to technology by automatically assuming that tech is good and “analogue” practices are bad. (I’d like to assume that any decent Ed Designer/Tech knows this but it bears repeating and I’m sure we’ve all encountered “thought leaders” with this take on things).

“we can find ourselves collapsing into a form of ‘digital dualism’ which assumes a clear binary between digital and analogue / print-based practices (?)…I would argue there are two problems with this. First, that it suggests educational and social practice can be unproblematically categorised as one or the other of these, where from a sociomaterial perspective I would contend that the material / embodied, the print-based / verbal and the digital are in constant and complex interplay. Secondly, there perhaps is a related risk of falling into a ‘digital = student-centred, inherently better for all purposes’, versus ‘non-digital = retrograde, teacher-centred, indicative of resistance, in need of remediation’.” (Lesley Gourlay)

Another very common theme in the technology realm was the absolute importance of having reliable technology (as well as the right technology.)

“Make technology not failing* a priority. All technology fails sometime, but it fails too often in HE institutions. Cash registers in supermarkets almost never fail, because that would be way too much of a risk.” (Sonia Grussendorf)

When it comes to how technology is selected for the institution, a number of people picked up on the the tension between having it selected centrally vs by lecturers.

“Decentralize – allow staff to make their own technology (software and hardware) choices” (Peter Bryant)

Infrastructure is also important in supporting technologies (Alex Chapman)

Personally I think that there must be a happy medium. There are a lot of practical reasons that major tools and systems need to be selected, implemented, managed and supported centrally – integration with other systems, economies of scale, security, user experience, accessibility etc. At the same time we also have to ensure that we are best meeting the needs of students and academics in a host of different disciplines. and are able to support innovation and agility. (When it comes to the selection of any tool I think that there still needs to be a process in place to ensure that the tool meets the needs identified – including those of various institutional stakeholders – and can be implemented and supported properly.)

Finally, Andrew Dixon framed his VC elevator pitch in terms of a list of clear goals describing the student experience with technology which I found to be an effective way of crafting a compelling narrative (or set of narratives) for a busy VC. Here are the first few:

- They will never lose wifi signal on campus – their wifi will roam seemlessly with them

- They will have digital access to lecture notes before the lectures, so that they can annotate them during the lecture.

- They will also write down the time at which difficult sub-topics are explained in the lecture so that they can listen again to the captured lecture and compare it with their notes. (Andrew Dixon)

Some practical solutions

Scattered liberally amongst the discussions were descriptions of practical measures that people and institutions are putting in place. I’ll largely let what people said stand on its own – in some cases I’ve added my thoughts in italics afterwards. (Some of the solutions I think were a little more tongue in cheek – part of the fun of the discussion – but I’ll leave it to you to determine which)

Culture / organisation

Our legal team is developing a risk matrix for IT/compliance issues (me)

(We should identify our work) “not just as teaching enhancement but as core digital service delivery” (Amber Thomas)

“we should pitch ‘exposure therapy’ – come up with a whole programme that immerses teaching staff in educational technology, deny them the choice of “I want to do it the old fashioned way” so that they will realise the potential that technologies can have…” (Sonja Grussendorf)

“Lets look at recommendations from all “strategy development” consultations, do a map of the recommendations and see which ones always surface and are never tackled properly.” (Sheila MacNeill)

“Could this vision be something like this: a serendipitous hub of local, participatory, and interdisciplinary teaching and learning, a place of on-going, life-long engagement, where teaching and learning is tailored and curated according to the needs of users, local AND global, actual AND virtual, all underscored by data and analytics?” (Rainer Usselman)

“…build digital spaces to expand our reach and change the physical set up of our learning spaces to empower use of technology…enable more collaborative activities between disciplines” (Silke Lange)

“we need a centralised unit to support the transition and the evolution and persistence of the digital practice – putting the frontliners into forefront of the decision making. This unit requires champions throughout the institutions so that this is truly a peer-led initiative, and a flow of new blood through secondments. A unit that is actively engaging with practitioners and the strategic level of the university” (Peter Bryant)

In terms of metrics – “shift the focus from measuring contact time to more diverse evaluations of student engagement and student experience” (Silke Lange)

“Is there a metric that measures teaching excellence?… Should it be designed in such a way as to minimise gaming? … should we design metrics that are helpful and allow tools to be developed that support teaching quality enhancement?” (David Kernohan) How do we define or measure teaching excellence?

“the other thing that we need to emphasise about learning analytics is that if it produces actionable insights then the point is to act on the insights” (Amber Thomas) – this needs to be built into the plan for collecting and dealing with the data.

Talking about the NSS (National student survey) – “One approach is to build feel-good factor and explain use of NSS to students. Students need to be supported in order to provide qualitative feedback” (David Kernohan) (I’d suggest that feedback from students can be helpful but it needs to be weighted – I’ve seen FB posts from students discussing spite ratings)

“We should use the same metrics that the NSS will use at a more granular levels at the university to allow a more agile intervention to address any issues and learn from best practices. We need to allow flexibility for people to make changes during the year based on previous NSS” (Peter Bryant)

“Institutional structures need to be agile enough to facilitate action in real time on insights gained from data” (Rainer Usselmann) – in real time? What kind of action? What kind of insights? Seems optimistic

“Institutions need at the very least pockets of innovation /labs / discursive skunk works that have licence to fail, where it is safe to fail” (Rainer Usselmann)

“Teachers need more space to innovate their pedagogy and fail in safety” (Silke Lange)

“Is it unfair (or even unethical) to not give students the best possible learning experience that we can?…even if it was a matter of a control group receiving business-as-usual teaching while a test group got the new-and-improved model, aren’t we underserving the control group?” (me)

“I can share two examples from my own experiences

An institution who wanted to shift all their UG programmes from 3 year to 4 year degrees and to deliver an American style degree experience (UniMelb in the mid 2000s)

An institution who wanted to ensure that all degree programmes delivered employability outcomes and graduate attributes at a teaching, learning and assessment level

So those resulted in;

a) curriculum change

b) teaching practice change

c) assessment change

d) marketing change ” (Peter Bryant)

“One practical option that I’m thinking about is adjusting the types of research that academics can be permitted to do in their career path to include research into their own teaching practices. Action research.” (Me) I flagged this with our Associate Dean Education yesterday and was very happy to hear that she is currently working on a paper for an education focussed journal in her discipline and sees great value in supporting this activity in the college.

“I think policy is but one of the pillars that can reinforce organisational behaviour” (Peter Bryant)- yes, part of a carrot/stick approach, and sometimes we do need the stick. Peter also mentions budgets and strategies, I’d wonder if they don’t change behaviour but more support change already embarked upon.

Technology

“let’s court rich people and get some endowments. We can name the service accordingly: “kingmoneybags.universityhandle.ac.uk”. We do it with buildings, why not with services?” (Sonia Grussendorf) – selling naming rights for TELT systems just like buildings – intriguing

We need solid processes for evaluating and implementing Ed Tech and new practices (me)

Pedagogical

“Could creating more ‘tailored’ learning experiences, which better fit the specific needs and learning styles of each individual learner be part of the new pedagogic paradigm?” (Rainer Usselman) (big question though around how this might be supported in terms of workload

“At Coventry, we may be piloting designing your own degree” (Sylvester Arnab)

“The challenge comes in designing the modules so as to minimise prerequisites, or make them explicit in certain recommended pathways” (Christopher Fryer)

I went on to suggest that digital badges and tools such as MyCourseMap might help to support this model. Sylvester noted that he is aware that “these learning experiences, paths, patterns, plans have to be validated somehow” Learner convenience over pedagogy – or is it part of pedagogy in line with adult learning principles of self-efficacy and motivation. In a design your own degree course, how do we ensure that learners don’t just choose the easiest subjects – how do we avoid the trap of having learners think they know enough to choose wisely?

“digital might be able to help with time-shifting slots to increase flexibility with more distributed collaboration, flipped teaching, online assessment” (George Roberts)

“At UCL we are in the midst of an institution-wide pedagogic redesign through the Connected Curriculum. This is our framework for research-based education which will see every student engaging in research and enquiry from the very start of their programme until they graduate (and beyond). More at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/teaching-learning/connected-curriculum

The connected bit involves students making connections with each other, with researchers, beyond modules and programmes, across years of study, across different disciplines, with alumni, employers, and showcase their work to the wider world…

There is strong top-down support, but also a middle-out approach with faculties having CC fellows on part time secondments to plan how introduce and embed the CC in their discipline.

From a TEL perspective we need to provide a digital infrastructure to support all of this connectivity – big project just getting going. Requirements gathering has been challenging… And we’re also running workshops to help programme and module teams to design curricula that support research-based and connected learning.” (Fiona Strawbridge) – liking this a lot, embedding practice. What relationship do these fellows have with lecturers?

“I am imagining that my research, personal learning environment would fit perfect with this approach as I am thinking the PLE as a toolbox to do research. There is also a potential there to engage student in open practice, etc.” Caroline Kuhn

“There may be a “metapedagogy” around the use of the VLE as a proxy for knowledge management systems in some broad fields of employment: consultancy, financial services, engineering…” (George Roberts) (which I’d tie to employability)

“We need to challenge the traditional model of teaching, namely didactic delivery of knowledge. The ways in which our learning spaces are currently designed -neat rows, whiteboard at front, affords specific behaviours in staff and students. At the moment virtual learning spaces replicate existing practices, rather than enabling a transformative learning experience. The way forward is to encourage a curricula founded on enquiry-based learning that utilise the digital space as professional practitioners would be expected to” (Silke Lange) – maybe but none of this describes where or how lecturers learn these new teaching skills. Do we need to figure out an evolutionary timeline to get to this place, where every year or semester, lecturers have to take one further step, add one new practice?

“Do not impose a pedagogy. Get rid of the curricula. Empower students to explore and to interact with one another. The role of the teacher is as expert, navigator, orienteer, editor, curator and contextualisor of the subject. Use heuristic, problem-based learning that is open and collaborative. Teach students why they need to learn” (Christopher Fryer)

This is but a cherry-picked selection of the ideas and actions that people raised in this hack but I think it gives a sense of some of the common themes that emerged and of the passion that people feel for our work in supporting innovation and good practices in our institutions. I jotted down a number of stray ideas for further action in my own workplace as well as broader areas to investigate in the pursuit of my own research.

As always, the biggest question for me is that of how we move the ideas from the screen into practice.

Further questions

How are we defining pedagogical improvements – is it just strictly about teaching and learning principles (i.e. cognition, transfer etc) or is it broader – is the act of being a learner/teacher a part of this (and thus the “job” of being these people which includes a broader suite of tools) (me)

What if we can show how learning design/UX principles lead to better written papers by academics? – more value to them (secondary benefits) (me)

“how much extra resource is required to make really good use of technology, and where do we expect that resource to come from?” (Andrew Dixon)

Where will I put external factors like the TEF / NSS into my research? Is it still part of the organisation/institution? Because there are factors outside the institution like this that need to be considered – govt initiatives / laws / ???

Are MOOCs for recruitment? Marketing? (MOOCeting?)

“How do we demonstrate what we do will position the organisation more effectively? How do we make sure we stay in the conversation and not be relegated to simply providing services aligned with other people’s strategies” (arguably the latter is part of our job)

“How do we embed technology and innovative pedagogical practices within the strategic plans and processes at our institutions?” (Peter Bryant)

Further research

Psychology of academia and relationships between academic and professional staff. (Executive tends to come from academia)

“A useful way to categorise IT is according to benefits realisation. For each service offered, a benefits map should articulate why we are providing the service and how it benefits the university.” (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benefits_realisation_management ) (Andrew Dixon)

Leadership and getting things done / implementing change, organisational change

How is organisational (particularly university) culture defined, formed and shaped?

Actor-network theory

Design research

Some ideas this generated for me

Instead of tech tool based workshops – or in addition at least – perhaps some learning theme based seminars/debates (with mini-presentations). Assessment / Deeper learning / Activities / Reflection

Innovation – can be an off-putting / scary term for academics with little faith in their own skills but it’s the buzzword of the day for leadership. How can we address this conflict? How can we even define innovation within the college?

What if we bring academics into a teaching and learning / Ed tech/design support team?

Telling the story of what we need by describing what it looks like and how students/academics use it in scenario / case study format offers a more engaging narrative

What is the role of professional bodies (E.g. unions like the NTEU) in these discussions?

Are well-off, “prestigious” universities the best places to try to innovate? Is there less of a driving urge, no pressing threat to survival? Perhaps this isn’t the best way to frame it – a better question to ask might be – if we’re so great, what should other universities be learning from us to improve their own practices? (And then, would we want to share that knowledge with our competitors)

“I was thinking about the power that could lie behind a social bookmarking tool when doing a dissertation, not only to be able to store and clasify a resource but also to share it with a group of likeminded researcher and also to see what other have found about the same topic.” (Caroline Kuhn) – kind of like sharing annotated bibliographies?

Bigger push for constructive alignment

I need to talk more about teaching and learning concepts in the college to be seen as the person that knows about it

In conclusion

I’d really like to thank the organisers of the Digital is not the future Hack for their efforts in bringing this all together and all of the people that participated and shared so many wonderful and varied perspectives and ideas. Conversation is still happening over there from what I can see and it’s well worth taking a look.