Easily one of my favourite things about working at a university is the rich range of speakers that come to share ideas with us. This week alone we have presentations for International Women’s Day and lectures on vote buying in Indonesia, Public Private Partnerships in infrastructure, Poverty alleviation in Brazil and Argentina, the Paris Climate Talks, the 2016 Defence White paper and exploring fertility of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

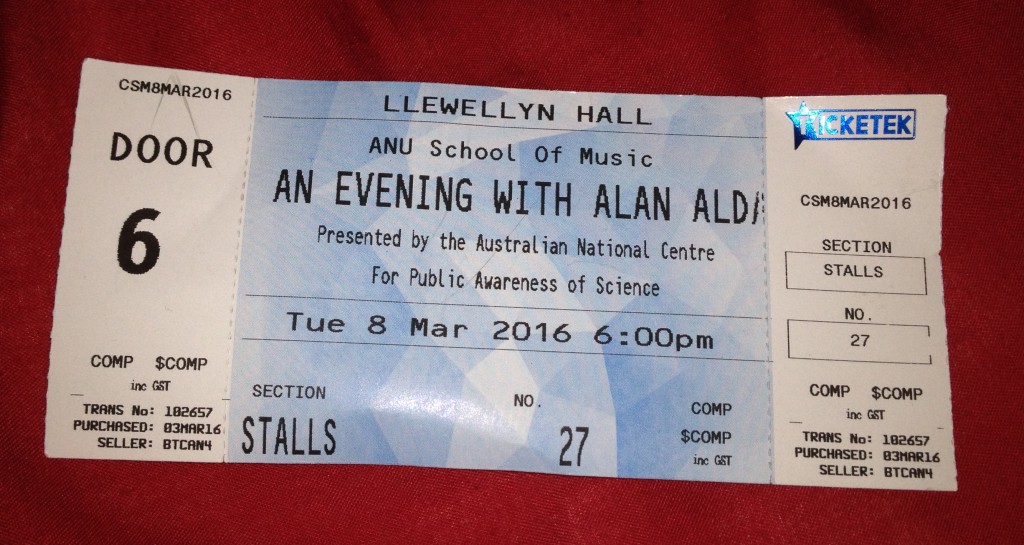

Last night we also had Alan Alda talking about science communication. He was amazing.

This isn’t something that I knew about him before but this is a long standing passion of his. He is the co-founder of the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University and hosted a tv series – Scientific American Frontiers – interviewing scientists around the world for more than a decade.

Funnily enough, I suspect that like many of the 1300+ people in the audience, that wasn’t my primary reason for going to the talk. (Though it did seem interesting in itself). Whether for his performances as Hawkeye in M*A*S*H, Sen. Arnold Vinick in The West Wing or most recently Pete in Louis CK’s Horace and Pete, Alda is an astounding actor and communicator and has won over many fans in his long career.

While Alda spoke directly about science communication, it was clear to me that everything he said could just as easily be applied to teaching practice, particularly in higher ed where there can be a tendency to get caught up in highly complex and dry technical language. (Which isn’t to say that this isn’t needed or that academics and scholars don’t need common specific terminology to communicate sophisticated content, more that particularly when introducing new concepts, it can be helpful to think about other cognitive processes that aid in learning)

In a nutshell, what I took away from the presentation was:

- It’s ok to use plain English to explain concepts that the audience (student) isn’t familiar with

- People retain information far better when it is attached to an emotion that they have experienced in receiving it.

- Presenting your information as a narrative with a degree of showmanship will enhance engagement.

- When you know too much about something, it can be easy to forget how to see it from the perspective of a novice (and adjust your explanation accordingly)

Alda illustrated all of these core ideas with stories and demonstrations that were exciting (a desperate rush for emergency surgery in Chile), disgusting (children thrown in a river in medieval times to ensure that public events stayed in public memory), amusing (an exercise in getting the audience to guess a song by having someone tap it out on the lectern) and truly sad (doomed lovers doing a heartbeat experiment)

Much of what he had to say resonated deeply with many ideas related to cognition and learning over the years that have sparked my interest in scenarios, game based learning and gamification. While he didn’t drill down into which researcher showed what, there is a wealth of research out there that has demonstrated the value of the emotional and personal connections that presenters/scientists/teachers can add to their teaching practices to make them resonate more with an audience.

When asked which areas of science have the biggest problems with this, he made the point that what the anti-vaccination campaigners on their side (as far as persuasion goes) is the emotion and the intimacy of their personal stories. No idea how to counter this but I think he’s right.

There was also an additional point raised (timely on International Women’s Day) about how women in science sometimes feel that they have to present a more dispassionate and impersonal face to their audiences to avoid the stereotypes of “emotional” women. Again, no solutions but an interesting point.

The Q&A component of the talk was filmed and here it is