I just realised that Part 1 of these posts had been sitting in my drafts folder – waiting for ??? – so if it seems like I’ve had an incredibly productive burst of writing, yeah nah. (Which isn’t to say that I don’t have a fair bit to say about this book now, as I have found it particularly helpful)

One thing I have learned, sadly, is that the Kindle doesn’t sort “highlights” (selections that I’ve made in the text) by chapter, so my notes aren’t as useful to me as I might’ve hoped. I’ll know to add notes to the highlights as well next time, listing the chapter. (It is still pretty handy being able to collate them in the kindle.amazon.com/your_highlights page though)

Chapter 2: Researching Universities.

Trowler looks here at some of the knowledge and data issues that we face when researching in universities. Primarily the nature of the different types of knowledge present – implicit and explicit.

Implicit relates to practice knowledge (a.k.a phronesis) that has been developed through experience and which can be harder to express in words. Things like how to deliver a rigorous and yet engaging lecture. Because it is lived knowledge, it can be argued that it carries more legitimacy than that which has come from theory. At the same time, it will be very important to remember that there can often be a gap between people’s perspectives of their actions and the actions themselves.

On the other side we find propositional or technical knowledge, which is more like your old fashioned book learning. Easier to express and generally more objective but if we take into consideration the fact that unis exist in different contexts and can have their own quirks, this knowledge is likely to be useful in different applications.

Trowler references Blackler (1995), who

distinguishes between five types of knowledge identified in the organizational literature: embodied; embedded; embrained; encultured and encoded. These terms describe, respectively, knowledge which lies in muscle memory and is seen in skilled physical performances (performative knowledge); that which is located in systematic routines; knowledge which lies in the brain (cognition); that which is located in shared meaning systems; and finally knowledge which is encoded in text of various sorts.

For the research that I’m considering – which currently seems to be drifting toward the role of the university as a whole (or as an “ecology” if you will), I can see that there may be value in most of these kinds of knowledge. I get the feeling that there is definitely going to be a need to consider some of the theories relating to organisations and management.

In a nutshell, I need to be mindful of the ontological and epistemological questions that come up relating to the nature of reality and of knowledge and have an answer ready for questions about how I have done so.

Chapter 3: Research design, data collection and theory

This is a major section for me as I’ve been out of the formal research loop for a long time. If you don’t read anything else in this book (and methodology is important to you), read this. This chapter runs through major methodological approaches, offering up pros and cons for all of them. Ultimately Trowler’s own research took an ethnographic case study approach in a single site and drew from four sources of data: “interviews, observant participation, documents generated within and without the institution and other studies of it”.

Having stepped us through the alternatives, Trowler’s case for his approach in his research appears sound. (Of course, at this stage I’m going off intuition rather than experience but my understanding is that as long as you can make a strong/valid enough argument for your methodology, you can pretty much do what you like)

He anchors this discussion with a comparison of two ontological perspectives (whether they exist as a dichotomy or as points on a spectrum is debatable, of course). There is the “realist” approach (more quantitative, tied to “correlations of a generalisable nature”) and the “social constructivist” (more qualitative, reality is more subjective, more specific but less generalisable).

A key question raised – and certainly one that I’ll need to consider – is that of single site vs multi site research. Beyond the basic logistical issues, there is also (for me) the matter of one site being insider research and another being outsider research. (Even though if I was to go with a second and even a third site, I have connections and relationships in both).

To be clearer, at this stage I’m considering primarily researching within my own university (ANU) and possibly the neighbouring University of Canberra. A third option could be my former employer, the Canberra Institute of Technology, a Vocational Education and Training provider. On the one hand, this would introduce a lot more variables to the things being examined – well-resourced, research “elite” university vs emerging, “standard” university vs resource-challenged teaching focused adult education provider. All of these variables will necessarily shape the data collected and the questions asked. On the other hand, being able to compare approaches to similar questions (how can we better support TELT practices) could well be more illuminating.

Trowler identifies 6 type of comparative projects of interest:

1. The factors influencing the success or otherwise of an innovation (for example around virtual learning environments’ deployment and use)

2. Approaches to management and leadership and their effectiveness

3. The implementation of a national policy

4. Compliance (or otherwise) with national quality (or other) guidelines

5. Professional practices in a discipline or field of study

6. Student responses to an innovation

To be honest, the added complexity feels like an overreach at this juncture – I’d rather do something simpler well. It does open the door for further research down the track of course.

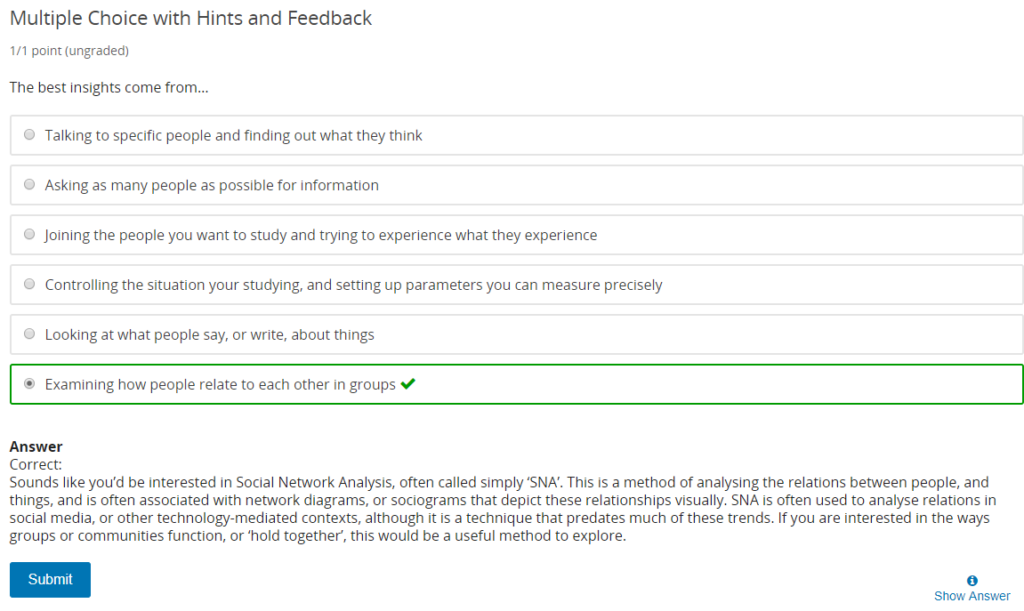

Of the methodological approaches discussed, I’d summarise them as follows:

Ethnographic – Participant observation

Researcher ‘lives with the natives’ for prolonged periods of time, fly on the wall type observation, often starts froma particular standpoint, “should be for people and not just about them”, language and textual objects vital,

Action research

Focused on solving particular problems, researcher is often a practitioner, iterative processes

Evaluative research

“Evaluative research in higher education aims to attribute value and worth to individual, group, institutional or sectoral activities happening there”. Care needs to be taken to ensure that it makes a larger contribution (theoretical/methodological/professional) to knowledge in the academic world

Hypothesis testing

Often trying to replicate findings of other studies, may try to improve on methodological flaws in prior studies, applying and extending theory

From here, Trowler moves on to discussing the importance of connecting theory to research. From what I can see, it seems to be partially as a way of finding a standpoint and a set of questions and partially as a way of testing some of the hypotheses.

He offers a solid overview of the characteristics of theory:

1. It uses a set of interconnected concepts to classify the components of a system and how they are related.

2. This set is deployed to develop a set of systematically and logically related propositions that depict some aspect of the operation of the world.

3. These claim to provide an explanation for a range of phenomena by illuminating causal connections.

4. Theory should provide predictions which reduce uncertainty about the outcome of a specific set of conditions. These may be rough probabilistic or fuzzy predictions, and they should be corrigible – it should be possible to disconfirm or jeopardize them through observations of the world. In the hypothetico-deductive tradition, from which this viewpoint comes, theory offers statements of the form ‘in Z conditions, if X happens then Y will follow’.

5. Theory helps locate local social processes in wider structures, because it is these which lend predictability to the social world.

6. Finally, theory guides research interventions, helping to define research problems and appropriate research designs to investigate them.

One of the goals of theory seems to relate to being able to “render the normal strange”. A challenge to face as an insider researcher – and particularly in the face of information sources that will come with their own biases and preconceptions – is to maintain that objectivity.

One way of addressing this is by “the application of Stenhouse’s (1979) notion of the ‘second record’ (the use of a detailed understanding of meaning systems to ‘read’ interview data) to this kind of secondary data about the institution.”

Trowler mentions that he probably collected too much data which caused problems in the data analysis phase – no idea how to deal with that but this is something that I will look for in my further reading about research practices.

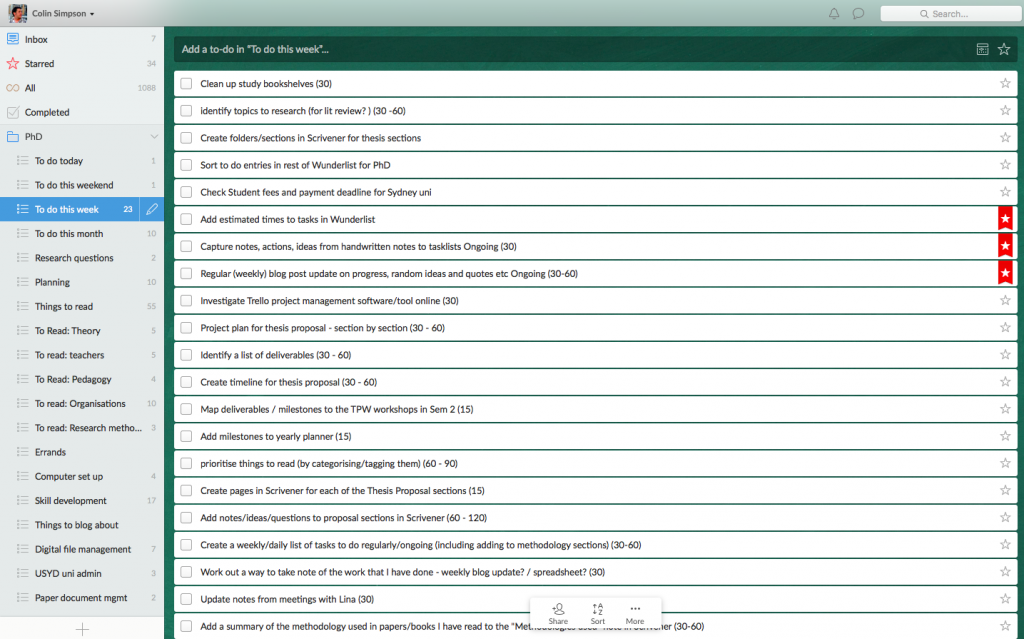

This chapter also includes a solid description of the methodology that he used in his own PhD research – I think what I’m going to need to do is to create a spreadsheet or database outlining different methodologies – that should be particularly helpful. (Already partially discussed above).

2977232

{:7UZ2XN7W}

1

apa

50

default

595

https://www.gamerlearner.com/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/

2977232

{:JZG4R2EE}

1

apa

50

default

595

https://www.gamerlearner.com/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/

2977232

{:MGE3RG48}

1

apa

50

default

595

https://www.gamerlearner.com/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/